Australian Indigenous Film and Television - New Frames for Understanding

In the past decade, we have witnessed an explosion of Indigenous-authored feature films and television dramas that have been widely celebrated and critically lauded as some of the most distinctive storytelling in Australian screen history. These works did not emerge from ‘nowhere’. They are part of a history of Australian Indigenous filmmaking that dates back to the 1970s and includes to date more than 600 shorts, documentaries, features and TV drama series. 160 of these works were funded by the Indigenous Department of Screen Australia, which plays a leading role in supporting Indigenous film and television making since 1993. These works have emerged as part of a broader Indigenous cultural renaissance in particular organizations, sites and companies. The Indigenous screen production sector operates within the local industry while remaining culturally distinct through funding and policies that support Indigenous creative control.

Our research has focused on the shape of Australian Indigenous film and television, as it has been constituted by overlapping and intersecting frames of policy, production and reception. This website presents our published research. It is also designed to make the extensive amount of data we have collected and curated available for further studies and to foster the sharing of ideas, knowledge and new frames of understanding. In summary, we found that film and television with Indigenous Australians in key creative roles:

- - leads local industry in innovative practice and initiatives

- - is of major global importance as an emergent cultural and political form

- - unearths hidden histories that contest dominant narratives of Australia’s colonial past

- - plays rich and varied roles for Indigenous audiences and communities (across Australia and around the world)

- - has potential, in many instances, to transform the ways in which non-indigenous audiences experience film and television.

Research Principles and Indigenous Cultural Intellectual Property Rights

This website acknowledges Indigenous filmmaking as a process in which relationships are central, and all productions relationally occur within a landscape that includes the more-than-human world. We are using the term Indigenous rather than Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander, or First Nations to acknowledge Indigenous filmmaking in the land now known as Australia as having its inception in social rights issues. As this website explores some of the work of the Indigenous Department of Screen Australia (SA), which developed from the Australian Film Commission’s (AFC) Indigenous Unit, the use of the word Indigenous is intended to position Australian Indigenous filmmakers within a global relational context of relevance, reciprocity, responsibility, and respect, informed by the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), especially Article 31.1, which is the foundation of Indigenous Cultural Intellectual Property Rights (ICIPR).(1)

Article 31

1. Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions.

In 2009, Terri Janke published Pathways & Protocols for the Indigenous Unit of Screen Australia, and states that it is ‘A filmmaker’s guide to working with Indigenous people, culture and concepts’(2) and was ‘produced to provide advice about the ethical and legal issues involved in transferring Indigenous cultural material to the screen.’(3) Pathways & Protocols is offered as a framework for filmmakers to take into consideration in their own productions, but as a concept it potentially positions relationships at the core of an ethical Indigenous filmmaking model, where

Accessible, practical and transparent protocols are the key to facilitating respectful filmmaking involving Indigenous cultural heritage. And protocols that enhance the positive experiences of filmmaking encourage further collaborative opportunities between cultures.(4)

Indigenous cultural values position process over product,(5)and conflicts with western industrial production models that prioritises product. We are proposing that the adoption of ICIP protocols in the Australian filmmaking industry may potentially inform an Indigenous ethics model that prioritises relationships, and be considered an important step in decolonising Australian industrial production models, as well as be an assertion of an Indigenous filmmaking paradigm that advocates for the rights of Indigenous peoples to self-determine, and promote Indigenous participation in national and international social discourse on how Indigenous peoples are represented and represent themselves in Australian film culture. The ICIP’s, however, are potentially more than a statement of respectful relationships between filmmakers and Indigenous peoples, but more a production process informed by Indigenous ethics that signal a shift from protocols to an applied ethics. Indigenous peoples’ cultural, philosophical and metaphysical knowledge and experience of the world challenges the object reality of western epistemology, the mechanics of the film camera and the material paradigms it represents, and the colonial power dynamics it reproduces within current industrial production models. As applied ethics, the ICIP’s would be transformative in guaranteeing the decolonization of settler colonial representation of Indigenous peoples, as well as generate culturally safe environments for Indigenous peoples to engage with western media.

We have chosen to use the term ‘Indigenous’ to acknowledge that all Indigenous people are in relationship and kinship with the natural environment, our laws, lore’s and customs positioning us in relationship to all beings; all things are sentient, the land is alive and has agency. We acknowledge that while Indigenous is a vehicle for talking about Australian Indigenous filmmaking in a global context, many Indigenous peoples prefer to use their language, nation names, and or identify themselves by country. For example, I am from Tjerangeri, what is known today as Stradbroke Island, off the coast of what is now called Queensland. I am Goenpul Yugerah Bundjalung Bidjara. For Indigenous peoples, the land is the source of Indigenous jurisprudence, and is central to the Indigenous worldview. It is the relationality between body and land that informs Indigenous sovereignty as a metaphysical, philosophical and spiritual understanding of place. These same values also inform displacement and emplacement. Indigenous sovereignty, as Moreton-Robinson tells us, is an embodied sovereignty, and while we as Indigenous peoples may have been displaced from our countries by western government policies, we need not be defined by this displacement as we carry our country with us;

Our sovereignty is embodied, it is ontological (our being) and epistemological (our way of knowing).(6)

Our land is a body, and our body is land. This propounds ideas such as ‘return to country’ as being more than a physical return to a physical place, instead it immediately becomes a multi-dimensional, multi-versal experience for Indigenous peoples. While a return to country is profoundly personal to each Indigenous person, ICIP protocols have provided a platform for Indigenous filmmakers to return to full immersion within worldviews that honour Indigenous epistemologies, ontologies, axiologies, methodologies and ethics. Tom Brislin tells us that ‘Along with ancestral lands, Indigenous Intellectual Property has been appropriated by colonizing dominant cultures … allowing it to be commodified at the expense of, and at a loss to, the original authors.’(7) However, the foundational philosophies of our storytelling must also inform the foundational values where media production claims to be in support of Indigenous cultural heritage communities. Moreton-Robinson argues that,

… Indigenous belonging challenges the assumption that Australia is postcolonial because our relation to land, what I conceptualize as an ontological belonging, is omnipresent, and continues to unsettle non-Indigenous belonging based on illegal dispossession.(8)

This ontological relationship to land that Moreton-Robinson describes as omnipresent, unsettling the settler, is deployed through the works of Indigenous filmmakers. It is here that the works by Indigenous film and television makers prove to be a valuable resource for Indigenous communities and the Australian filmmaking industry. By offering a sustained response to Australian settler colonialism framed by Indigenous policies, protocols, and informed by Indigenous worldviews, Indigenous filmmaking in Australia is, at its core, the inspired expression of Indigenous embodied sovereignty. This website is a contribution to the ongoing development of media production models informed by Indigenous ethics that must necessarily include the decoding of settler colonial representations of Indigenous peoples, by attending to settler colonial binaries such as authentic and inauthentic, and continue to address social justice issues and support Indigenous peoples' right to self-representation.

Dr Romaine Moreton, 2018.

ENDNOTES

- 04/04/2018 https://www.humanrights.gov.au/publications/un-declaration-rights-Indigenous-peoples-1

- Janke, Terri. Pathways & Protocols, 2009, Screen Australia, title page.

- ibid, p.4

- ibid

- ibid

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen. "Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous sovereignty matters (Australian Cultural Studies)", A&U Academic, 2007, p.2.

- 04/04/2018 http://caep-hu.sakura.ne.jp/files/Applied%20Ethics_2017.pdf

- Moreton-Robinson, Aileen, The White Possessive: Property, Power, and Indigenous Sovereignty, University of Minnesota Press, 2015, p.4.

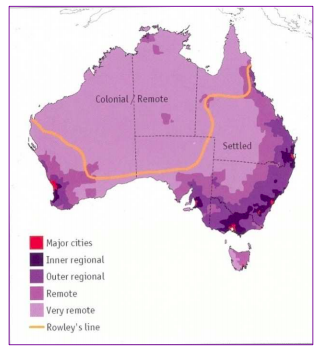

The inception of this website began in 2011 as a series of conversations with Indigenous filmmakers who were asked by researchers, Moreton and Davis, about key issues challenging Indigenous filmmakers in the Australian filmmaking industry today. One of the key concerns was how Indigenous media making above the Rowley line, defined by the social scientist CD Rowley as ‘colonial’ Australia, attracted more funding and critical analysis than those Indigenous media makers in what Rowley defined as the ‘settled area’ of Australia. This division between colonial and settled Australia has come to be known as the Rowley Line, and is better understood today as the line that demarcates remote and urban spaces in Australia. Rowley correlates this line with a statement of Aboriginal blood quantum, and the retention of an Aboriginal worldview correlating with blood quantum. That is to say, for Rowley, to be a so called full-blooded Aboriginal is equated with an authentic Aboriginal worldview;

In applying the term ‘colonial Australia’ to the area north of the dividing line in Map 1 … I have it in mind that in these northern and central regions the social relationships between the indigenous and the settler populations represent an earlier phase of changes brought by European settlement, and that there are many aspects remaining in the relations between the races which are typical of industrial colonialism. Aborigines of the full descent form the majority of non-Europeans in this region. Here, also, Aboriginal culture retains, to varying degrees, its significance for conduct and as a determinant of the Aboriginal ‘world view’ and value system.(1)

The Rowley Line, as a line that quantifies and qualifies Aboriginality, is also a temporal statement, where this condition of authenticity is predicated on ideas of the colonial zone heralding an earlier period of settler colonialism;

The differences between the social facts, broadly considered, correspond with historic phases, so that one seems, as it were, to go back as one approaches and passes our dividing line, from our ‘settled’ to our ‘colonial’ regions, into an earlier pattern of race relations.(2)

The Rowley Line is symbolic of constructed colonial binary, where Indigenous peoples are positioned as authentic or inauthentic, with moniker ‘part-Aboriginal problem’ applied to those viewed as being of part Aboriginal descent. The idea of the Indigenous body as a temporal anachronism where modernity and tradition cannot co-exist is a colonial binary that continues to impact Indigenous peoples today, and to which Indigenous filmmakers are constantly having to respond. Therefore, it is important to note that Indigenous filmmakers conduct relationships that defy and deny the burden of the Rowley Line that has occurred out of Australia settler colonialism. It is important than that we are able to understand that for Indigenous peoples, media making represents an opportunity to consolidate ancient knowledge, as well as to generate new knowledge at the interface of western media technology. It is also the means through which we are able to emphasise the ‘importance of relationships, that everything needs to be seen within the context of the relationships it represents.’(3) Irene Watson refers to this as ‘relational philosophy’ where Relational philosophy is embedded in indigenous knowledge systems; ‘knowledge belongs to a people and the people belong to a landscape.’(4). Producing media within an Indigenous paradigm also means that Indigenous key creatives, collaborators and participants are relationally accountable in ways that non-Indigenous peoples are not.

The works we have chosen as an area of research into Indigenous film and television are by screen content producers whose works collectively, but not exclusively, contribute to an emergent canon of Indigenous screen production informed by Indigenous principles through collective engagement with western media technology. It also purports to make transparent the power dynamics of western settler colonialism, the camera, the historical gaze of the ethnographer, and the mechanics of western industrial filmmaking.

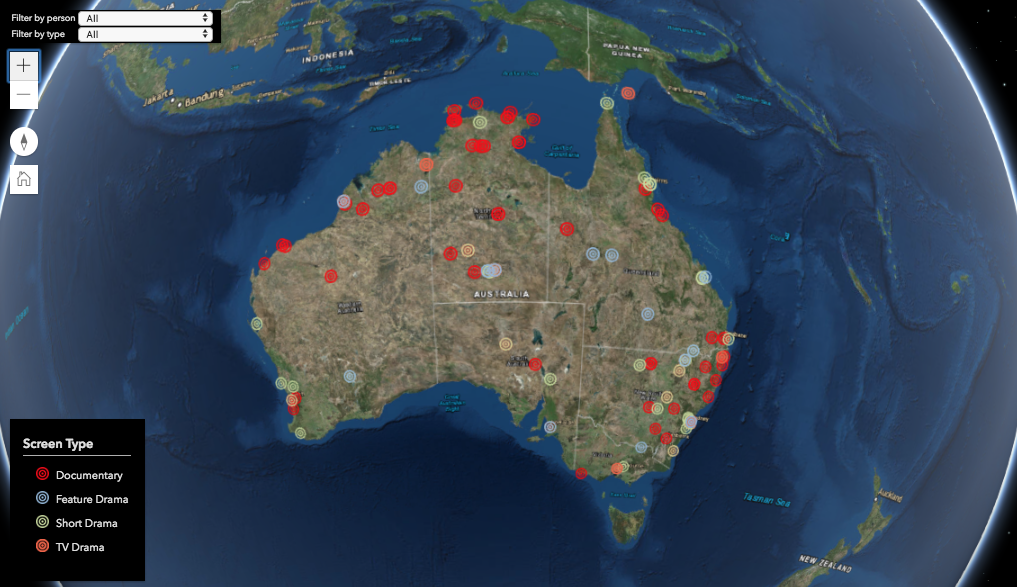

Interactive Map

Our interactive map visually contests the ‘remote-urban binary’ of the Rowley Line by providing information about a sample of more than 200 works written and directed by Indigenous screen creatives from across the country since the 1970s. It shows a network of storytelling in film and television that testifies to the diversity of Australian Indigenous identities and histories while reinforcing a unifying common goal. As filmmaker Darlene Johnson says about making films with actor David Gulpilil and his family,‘[t]he thing that brought me - an urban, fair skinned Blackfella from Bondi Beach - together with David Gulpilil - a traditional Aboriginal Yolngu man from Ramingining – is that we are both passionate about portraying Aboriginality on screen’. (Screening the Past, 2011)

ENDNOTES

- Rowley, C.D. The Remote Aborigine, Penguin Press, 1972, p. 13

- Rowley, C.D. Outcasts in White Australia, Australian University Press, 1971, p. viii

- Wilson, Sean. Research Is Ceremony, Fernwood Publishing, 2008, p. 43

- Watson, Irene. Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law, Taylor & Francis Ltd, 2016, p.13.

A major output of our research is Goenpul Jagara Bundjulung Dr Romaine Moreton’s practice-led, transmedia research project One Billion Beats. This work radically dismantles dominant apprehensions of Indigenous participation in film. It draws together Australian cinematic history with poetry and original score to privilege an Indigenous perspective on representations of Aboriginal people and culture by reclaiming ‘celluloid ancestors.’

Our publications draw attention to the many strategic initiatives by Indigenous Australian screen administrators and producers that have expanded opportunities for Indigenous screen production in the Australian screen industry and beyond from the groundbreaking TV documentary series First Australians to the award-winning feature films Samson and Delilah and The Sapphires. Davis’ publications on these and other mainstream productions in the 2000s argues that the Indigenous production of large-scale screen projects intended for a broad non-Indigenous audience is neither a ‘natural’ progression toward cultural assimilation (as some claim) nor a ‘new’ policy direction. It is a long-term strategic objective of Indigenous policy makers and producers, designed to ensure the sustainability of Indigenous cultural production; an actualization of Indigenous self-determination in and through screen production.

We have focused on Indigenous cultural values in film and television and the significance of filmmaking for Indigenous communities. Romaine Moreton’s reflections on the making of her film The Farm and Moreton and Davis’ close analysis of Mitch Torres’ documentary Whispering In Our Hearts show how Indigenous cultural values can be embedded in both form and content. Davis’s analysis of the films of Darlene Johnson looks at how Johnson’s works contribute to Australian cinema history by bringing to light histories of the place of cinema in Indigenous peoples lives in both the city and the bush.

Chris Healy has a long-standing interest in the cultural history of relationships between Indigenous peoples and settler-colonial newcomers to this land. He has explored these histories in From the Ruins of Colonialism (1997) and Forgetting Aborigines (2008). His analysis of television series Alcheringa is, in part, an attempt to see screen production as having involved, indigenous people from the beginning, if, initially, only as objects of fascination. He is currently completing a book on ‘travelling television’ in which indigenous people are not only a central concern but important producers ranging from series such as Bush Mechanics (2001) to Art+Soul (2010-2014), created by Indigenous curator, Hetti Perkins.

Matteo Dutto’s published research on the docu-drama Jandamarra’s War demonstrates the insights that can be gained through close analysis of cultural protocols and production processes. A book version of his PhD thesis, ‘Legacies of Resistance: Australian Indigenous Resistance Leaders in Indigenous Film, Theatre and Literature’, is forthcoming with Peter Lang.

Our vision is a collaborative research community founded on Indigenous research principles and priorities. We value diverse knowledge and ideas and invite you to contribute your work to our ever expanding bibliography. We also welcome information about relevant interviews and related websites. See our contact details below.

We also recognise Indigenous audio-visual storytelling in all forms as a form of research and transmission of culture. Our aim is to add a viewing space to this website where Indigenous filmmakers can present short works. We will seek further funding to support this. In the meantime, please feel free to send us details of your work(s) for inclusion in our film list and map.

You can also join us on Facebook (see below) and contribute news.

We have gathered references to more than 800 relevant scholarly books, book chapters, journal articles and feature articles in magazines that we make available in our bibliography. These include access to digitized copies of articles on the early days of Indigenous filmmaking from the historically significant film journal Filmnews. We have another 438 reviews and news stories from print media that we are currently processing as a series of media dossiers on key films, past and current. We also have interviews to transcribe and publish, and we have publications in the pipeline.

Indigenous Cultural and Intellectual Property rights (ICIP) and applied ethics in Indigenous filmmaking is a research area of great importance to Romaine Moreton. She is continually researching in this area and is planning to develop much needed educational curricula and resources on ICIP.

There are many areas of Indigenous film and television that were beyond the scope of this project but need to be given research priority.

Indigenous television: We have not included non-fiction broadcast television such as news, comedy, lifestyle and sport. These formats as well as the introduction of the National Indigenous Television broadcasting service (NITV) in 2012 are hugely important for a full understanding of the Australian media landscape.

Indigenous producers initiatives: Our project has focused on Indigenous writers and directors. We recognise, however, that the role of producers and development of Indigenous-led production companies is a crucial means of sustained support for Indigenous creative control and requires greater understanding in order to complete the picture of Indigenous film and television making.

Conceptual design by Romaine Moreton and Therese Davis. Co-produced by Romaine Moreton, Therese Davis and Chris Healy with research assistance by Matteo Dutto. Production management by Therese Davis.

We wish to thank the following people for their research assistance over the past seven years: Cassi Plate, Sian Mitchell, Fincina Hopgood, Genna Burrows, Kirsten Stevens, Isabella McNeill.

This website is an output of two collaborative research projects:

- - Australian Research Council DP:140102789 ‘Contemporary Indigenous film and television: new frames of understanding’, Chris Healy (University of Melbourne), Therese Davis (Monash University) and Romaine Moreton (Monash University, 2014-16);

- - Screen Australia Research and Publications award, ‘Beyond The Remote-Urban Divide: Re-Mapping Australian Indigenous Screen Content and Its Audiences’, Therese Davis (Monash University) and Romaine Moreton (University of Newcastle).

Our Research Team

Goenpul Jagara Bundjulung scholar, film director and internationally recognised writer of poetry, prose and film, Romaine has developed a new decolonising framework to interrogate the Australian cinematic archive in the transmedia practice-led research project, One Billion Beats.

Dr Romaine MoretonDirector, First Nations and Outreach, Australian Film, Television and Radio School

Therese has published widely on Indigenous representation and participation in Australian cinema and television. Her research looks at the diverse ways in which Indigenous screen creatives are innovating screen genres to tell unique and challenging stories.

Swinburne University of Technology

Researching the place and significance of Indigenous media-making has allowed Chris to extend and deepen research he has published on relationships between Indigenous history and settler-colonialism in Australia for more than two decades.

Professor Chris HealyUniversity of Melbourne

Matteo’s work as lead research assistant has been an invaluable contribution to this project, informed by his own research on Indigenous multimodal and transmedia history-making practices.

Dr Matteo Dutto

Monash University